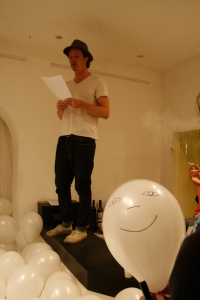

This was a text I read for Daniel Kemeny’s exhibition at Able Galerie in Berlin. He filled the room full of balloons and to see the work you had to climb around them, or just burst your way through. I wrote a story about balloons. I gave instructions at the beginning so when ever anyone heard a trigger word they’d do an action with a balloon.

Sheep – pick up a balloon

Sex – draw a face on it

String – tie the balloon to your arm

Sword – kill the balloon

Anyway, it was a bit of fun and this story is completely made up.

How your grandparents met

The story is set in the 1960s in Ireland in the middle of the Irish sexual revolution. It’s a story about balloons but it’s also about how my grandparents met.

In the sixties, while North Americans were having orgies up and down the west coast, the French were falling into loud orgasms whenever they heard the words Serge and Gainsbourg and the Germans just stayed nude for most of the decade, over on the farthest tip of Western Europe on a small island, called Ireland, a sexual revolution was also taking place.

One cool, autumn evening, all the women in the Irish countryside packed their belongings into bags and left.

They had read about the glamour of London and without even saying goodbye to the men who one day hoped to marry them, they left the countryside to follow their dreams. Like a fart in a phone box, the place cleared in an instant.

Now of course, not all of the women left, that would have been impossible. The mothers, the grandmothers, the gypsy women who might curse you as soon as kiss you, the girls young enough that they were still just boys, and the bearded ladies of which there were quite a few in the countryside stayed behind.

But the women. The real women. The kind that make young men write poetry, climb balconies and brush their teeth twice a day were all gone. That cool autumn evening the lazy bachelors went to bed thinking, I’ll ask her out tomorrow, and the next morning they were all gone. The Irish countryside was left in a terrible, terrible state of shock.

They’ll be back, the men in the bars said.

They’ll miss the place.

What’s London got that the countryside doesn’t they asked and then looked out from the dirty window as six types of cold black rain beat down upon the dark dirt road.

Of course they’ll be back, they told themselves. Electricity isn’t everything.

After two weeks there was still no sign of the girls and a heavy pessimism descended.

We’ve lost them forever, the men from the Irish countryside said. And in their anguish, despair and loneliness they looked for comfort in the one place they knew they would always find it.

Sheep.

The pretty ones. The ones who moved through the long grasses like models on catwalks and chewed the grass like they were eating lobster on some fine terrace in Moncao. The men would lean against the walls of the field and stare for hours lost in the sheep’s beauty and charm.

It became clear to the town leaders that unless something was done a whole generation of young Irishmen would be lost to wild animal romance.

They called for an emergency meeting. They had to bring the women back. But what would do it? There were discos in London but the only thing that came close to a disco ball in the countryside was when the clouds ran past the full moon.on stormy nights. No, they had nothing to compare with swinging London, but they did have the most powerful manipulator of human opinion known to man.

Mother’s Guilt.

They rounded up all the mothers in the villages and ordered them to start writing letters immediately filled with descriptions of illness, disease and crippled family pets. The mothers were resistant at first. They were happy that their daughters were living rock star lives in a foreign city. But when it was put to them that their sons were considering romantic liasons with farm animals, they soon started writing the letters.

It worked. Many of the women decided to come home.

But travel then, wasn’t like travel now. A trip from London to Dublin could take weeks to plan and by that stage the young men of the Irish countryside might have already fallen under the charms of the sheep.

They had to either kill all the sheep in the countryside or somehow find a temporary replacement for the women.

“What about the balloons?” one of the older men said and the room fell silent.

Now did you know that Ireland was the leading producer of balloons after WWII? Alongside butter, potatoes and whiskey, the Irish countryside was full of balloon factories. There’s a lot of spare wind in Ireland so it made sense. They produced simple white balloons and children all over the world played with them.

But when colour TV became popular in the late 50s, people lost interest in simple white balloons and nearly all of the factories closed down. Thousands upon thousands of balloons never ever got to see the light of day.

Could the balloons be a temporary replacement for Irish women?

They thought about it. There were many similarities between balloons and Irish country women. The skin colour was more or less the same. They both had that coldness of character where you could never understand if they were delighted or boiling with anger. Kissing a balloon was somewhat similar to kissing an Irish woman and having sex with a balloon was as equally impossible as with an Irish woman.

So they decided, to give every man in the village a balloon and a piece of string. They could attach it to their hand, take it with them where ever they went and this would keep them away from the temptations of the farmyard.

It worked. The men began to bond with their balloons. Some painted faces on them, others gave them wigs, and they all had the nicest sounding names imaginable. Eveline, Anne Marie, Sara Jessica, Florence and so on.

The men brought their balloons to the bar with them. The atmosphere was much improved. They were less aggressive towards each other. Their frustration had died and the animals lay their pretty, pretty heads upon the warm grass and slept easy at night.

Now while everyone else in the village knew that the balloons were just a temporary thing, for my grandfather a deeper bond was developing. He called his balloon Gale, because her movements reminded him of storms he’d seen out at see. And while the other men joked about their attachments, my grandfather only used the loftiest, most graceful language when it came to talking about his balloon.

She understands me, he used to say. Or I’d be lost without her, or she’s opened up my eyes to things I’d never have seen without her. My grandfather was a terrible sleeper. He spent the night at battle with the blankets. Gale had a calming effect on my grandfather. They did more than just share a bed, they shared their most intimate thoughts and desires.

“I always wanted to be a dancer,” my grandfather admitted to her one day.

Gale said nothing. But in this way she let him know that if he tried, he could do absolutely anything he wanted to.

And then, one bright afternoon in early Spring, the women started coming back. They had changed. They wore make up and their hair was unusually clean. The men got rid of their balloons. They all felt silly. Childish even. To think that they’d spent the whole winter going round with a little ball of air attached to their arms. My grandfather held tight to the string attached to Gale and wouldn’t let go.

“Ah will you ever get rid of that thing,” the other men said.

“Her name’s Gale,” my grandfather said.

The men felt bad for him.

“What do you see in her?” they asked.

“She never has a bad word about anyone,” he replied, “And that’s rare as gold in this day and age.”

It was around this time that my grandmother moved back to the village too. She had a round and lovely face and a body as skinny as a piece of string. She wasn’t much of a talker, in fact she barely said a word at all. And years of avoiding the two days of sun that God gifts the Irish every year, had left her skin as white as a balloon.

She saw my grandfather out in the fields, digging a hole. Gale, the balloon, was attached to his arm as ever. She was instantly attracted to this strange and stubborn individual. But my grandfather only had eyes for Gale. He said hello to my grandmother as she passed but wouldn’t look her in the eye.

Now there is nothing in this world more fearsome than an Irish woman when she sets her eyes upon her man. Two armies couldn’t stop her. And my grandmother was a very determined woman. The story goes that when she was only eight she refused to eat her broccoli and was forced to stay at the table. My grandmother stayed there for a whole ten days until her parents finally gave in and took away the broccoli. Upon victory she collapsed and the doctor had to be called for. Her family said that it would be easier to move the world than to move her.

Every morning throughout winter she took a detour in order to pass the field where my grandfather was digging, and every morning she’d stop and say hello to him. In this subtle and determined way, she slowly won his attention.

Now digging holes is a very popular pastime in the Irish countryside. Some men go from their youth to old age digging the same whole and never get tired. Ireland is a land of epic holes. My grandfather loved his hole. It was more than just dirt and stone and worms, it was like a good friend. He had grown up in that hole. It had taught him to become a man and it had won his trust. Now, rare as it is in other places, in Ireland, sometimes holes talk.

One day while my grandfather was digging, the hole opened up its mouth and spoke.

“You’re wasting your time,” the hole said. My grandfather was so shocked that he fell on his ass.

The hole continued to talk.

“You need to find yourself a woman.”

My grandfather knew that his hole was one of the oldest and wisest in all Ireland, and that its words were to be believed.

The next morning when my grandmother was walking by the field, my grandfather went over to talk to her.

“Do you like walking?” he said to her. My grandfather was a charmer from the old school.

“I do,” said she.

“Do you like walking in company?” he said to her.

“Its nice,” she replied.

“Can I take you for a walk this evening?” he asked.

“You can,” said she.

That evening my grandparents had their first date. They went walking. Gale came too. Maybe there was something in the air or it was actual jealousy but she moved between my grandparents with an aggression that my grandfather had never seen before. It was as if she sensed the end was near.

My grandfather sensed it too. He needed to make a decision. He made it that night he stared in the mirror and the words of Oscar Wilde ran through his strong, country head.

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word.

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

And that’s how my grandparents met.